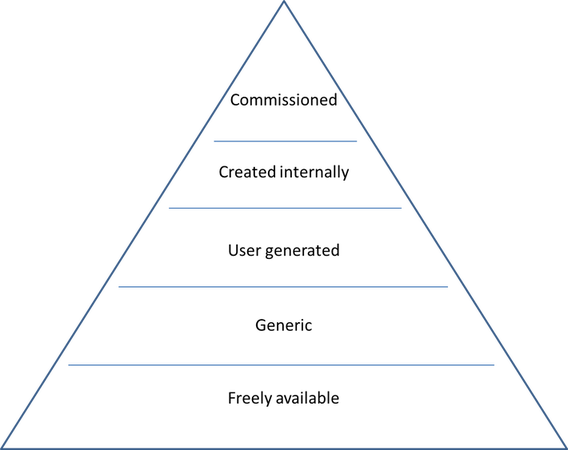

The learning content pyramid

Question: are organisations now creating more or less of their own learning content than they used to?

Answer: I don’t know. And I’m not sure anyone else does, either. In fact, I don’t believe any industry data on this exists. That may be reasonable – after all, the definition of ‘learning content’ is slippery thing – but it still rankles.

An animated conversation about this with several providers and users of learning content a few weeks ago at Sally Ann Moore’s iLearn Forum in Paris was fascinating but inconclusive. Every possible opinion was expressed, and no conclusion reached.

Of course the conversation took a long time wandering around the different types of ‘content’ that we might be talking about. Did we mean classroom courses? Online courses? MOOCs? Free stuff from the internet? Generic stuff? User-generated content?

To try and make some sense of the different types of content I sketched out this pyramid of different types of content, the lowest part of the pyramid being where there is the greatest volume –>

By ‘content’, I’m referring to materials people learn from. This includes reference materials and courses. It could be on any medium – Google plus, a video on your phone or a book. To be clear: I am not suggesting that content creation/sourcing and maintenance is the only role of L&D.

From the bottom of the pyramid the five layers are:

Freely available – The internet provides an almost unlimited set of resources to draw on for learning. The trick is to choose the right ones. In an LSG webinar recently Virgin Media’s Mike Leavy showed (among other things) how they incorporate free content from on their corporate Cornerstone OnDemand LMS (see at 41:30 in the video). And this goes beyond a few links to YouTube. It includes iTunes U, free courses from MOOC suppliers Coursera and Udemy, talks from TED and lessons from the Khan Academy as well as free online courses from the Open University’s Learning Space.

With online courses now available for free from the world’s leading universities, why would you not include MOOCs in your available content? As the range of these offerings widen (see my previous blog on MOOCs), the challenge for L&D here is to move from solely creating content to sourcing it – in particular in filtering to make the most useful stuff visible (see my previous blog on filtering as one of L&D’s 4 key content skills).

Generic – There is a strong, global market for online learning materials, so strong that before writing anything, L&D must always ask who else might have already produced it. When he first arrived at Lloyd’s as CLO, one of the first things Peter Butler did was to stop his L&D team producing courses on topics such as Microsoft Excel and Word. The company already had a subscription to an online course provider, meaning that these courses were available for use at no additional marginal cost. Maybe these weren’t exactly the content and quality the L&D team would have liked, but they were certainly good enough. The L&D team’s time was better spent doing higher value work.

And ‘generic’ needn’t mean ‘poor quality’. Video Arts has produced high-quality generic management training materials for more than 20 years. And neither need ‘generic’ mean ‘non-sector specific’ either. When Ray O’Connor produced an anti money-laundering course at his legal firm, he realised that it would be useful outside the organisation, and made it more widely available. It’s always worth checking with your L&D colleagues in your industry before you start writing anything.

And as well as the celebrated providers of online content such as Skillsoft there’s always the original generic content – books. The rise of the e-book removes the headache of providing and circulating physical books, leading to a rise in online books clubs that like that run by Shell Senior Innovation Adviser for Global HR Technologies Hans de Zwart where both the meetings and the books can be virtual.

User generated content (UGC) – UGC is all that great stuff which people naturally create in work that others can learn from – whether it’s explicitly designed for learning or not. A typical example would be Black & Decker’s use of short videos shared between members of its field sales team (see the CERTPOINT case study)

As well as very targeted material like this (most UGC videos are under 5 minutes long), UGC also includes chat sessions (like those from LSG webinars or Twitter #lrnchat meetings). I’d suggest that UGC is not entirely free, as we often like to believe. There may be no upfront cost, as there is with generic content, but it certainly takes time (and sometimes money) to set up and maintain the systems for sharing UGC, and we should never kid ourselves that opportunity cost is not a real cost.

Created internally – with so much else available for free or at low cost, the centrally generated materials we create must be context rich. This is where L&D adds value (again – see Interpretation – a crucial part of the L&D role)

BP’s internal ‘Moments of Truth’ programme, for example, uses video and story-telling to raise diversity and inclusion issues far more effectively than didactic approaches. (Click for the slides, or for the context of the 2012 Brightwave event “Beyond the Course” where I first saw this.)

‘Moments of Truth’ has very high production values, because that is appropriate for this subject: inclusion is a core issue for BP, and will remain part of employees’ learning for years to come.

Not all internally-generated content need be as beautifully prepared or even as emotionally engaging as ‘Moments of Truth’. The key differentiator is that it should be context rich, steeped in the reality of that particular organisation. When power tool manufacturer TTI wanted to improve efficiency in handling returned goods, it produced a clear online course with the 10 most common mistakes in handling returned goods. Sounds simple. It was. It also generated $33-$35m in savings over a 2 year period. (Click for the case study.)

Internally-generated materials don’t have to be fancy, just context rich and effective.

Commissioned – There will always be a place for high-quality commissioned content. The subject may require specialist knowledge beyond anyone in the organisation. It may also be a high-profile piece of work that demands great production values.

I sense, though, that commissioned content is an increasingly specialized field. As the cost of production has fallen, with great content creation and editing tools available at low-to-no cost, many of the barriers to creating good content have fallen. Global competition has also made this a tough market to be in. The bespoke content providers that remain have to offer a service where value rests on a combination of production and learning expertise as well as subject matter understanding.

As Clive Shepherd pointed out in 2008, Nick Shackleton-Jones originally proposed a three-layer model of content development at an eLearning Network event in the UK. The pyramid above has five layers, but it remains only a model. The map is not the territory.

If you choose to think of content in terms of a layered pyramid, I would love to hear your comments and insight. How many layers does your pyramid have? Where are you focusing your efforts now? And do you see your focus changing in the future? Perhaps if we engage in a broad conversation around this, we may be able to answer my original question: are we producing more or less of our own learning materials internally?